Two Ways of Filming a Crisis: |

In

the past few years, Brazil’s place in the media cycle has been divided between

the enthusiastic and the embarrassing: on the one hand, the nation’s status as

an emerging power among the BRICS group, and its soft diplomatic gestures as

host of both the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janeiro;

on the other, the massive anti-government demonstrations that accompanied those

two sporting events, the worsening spread of the Zika virus, the country’s real

economic stagnation after a period of continuous growth, and now the coup de grâce – this year’s political

coup that has seen the impeachment and deposition of president Dilma Rousseff,

amidst confirmations of pervasive corruption and bribery at various levels of

the political class. It is a tale of dashed hopes and diminishing returns, in

which the successive prophesies contained in the protestors’ hashtags –

#NãoVaiTerCopa (“There Will Be No World Cup”) and #NãoVaiTerGolpe (“There Will

Be No Coup”) – turned out to be false.

Large-scale

opposition to Brazil’s elected representatives began back in June 2013, with

protests against a proposed hike in bus fares in São Paulo. But since then,

myriad expressions of dissent have piggybacked on that initial complaint, with

widespread dissatisfaction about misspending of public funds coming from both

the left and right halves of the political spectrum. The targets of scorn have

shifted from the populist Partido dos Trabalhadores (or PT, The Workers’ Party)

under Rousseff to the current (interim) president, Michel Temer; the

generalised dishonesty that pervades the system has also engendered an

anti-political mood. Such is the variation of opposition to the government that

the forms of dissent have varied, too. What began as a series of peaceful,

coordinated protests in a number of cities throughout Brazil also transformed

into more radical ‘black bloc’ interventions and cyber-warfare, actions that

were met with severe police counter-offensives. (1)

Although

this complex narrative has reached leftist Anglophone audiences courtesy of

writers like Glenn Greenwald and Perry Anderson, reports from Brazil’s plutocratic

domestic press suggested a more simplistic state of affairs, a ‘two-dimensional

caricature’ of a series of events that they themselves had a hand in agitating.

(2) But recently, reflections on the country’s political instability have also

emerged in the ostensibly slower medium of cinema, with the protests making a relatively

quick impression in contemporary Brazilian filmmaking. Two films in particular

have taken as their points of departure the World Cup, and the protest

movements operating in the background of the tournament: Jovens infelizes ou um homem que grita não é um urso que dança (Young and Miserable or A Man Screaming Is

Not a Dancing Bear [Thiago B. Mendonça, 2016]) and Proxy Reverso (Reverse Proxy [Guilherme Peters and Roberto Winter, 2015]). And yet, although both films

adopt a militant oppositional stance towards the same government at precisely

the same point in history, their political and aesthetic strategies are

completely different: Young and Miserable focuses on a radical theatre troupe who are frustrated with the impact of their

art, and turn to violence instead, assassinating the governor of São Paulo

state by blowing him up in a collective suicide mission; Reverse Proxy is a film that takes place entirely on a computer desktop, and follows the exploits of a hacker, Davi (Leonardo Franša), who works with his friend Luis (Deyson Gilbert), to leak information confirming the manipulation of polling figures for the 2014 elections. Young and Miserable turns to the past, reviving both a radical politics and a cinema properly

belonging to the end of the sixties, while Reverse

Proxy orients itself more obviously to the present, a post-cinematic experiment in which the information economy could provide the

catalyst for revolution.

|

1. For a comprehensive overview of the political

turmoil of the past three years, see Perry Anderson, ‘Crisis in Brazil’, London Review of Books Vol. 38 No. 8 (21

April 2016), pp. 15-22. See also Fabiano Santos and Fernando Guarnieri, ‘From

Protest to Parliamentary Coup: An Overview of Brazil’s Recent History’, Journal of Latin American Cultural Studies,

Vol. 25, No. 4 (2016), pp. 485-494.

|

Two films addressing Brazil’s ongoing

political crisis quite directly and quite distinctly. But two

films that also interrogate the concept of cinema itself, and in which might be

discovered undercurrents of a different kind of politics, a politics of

intermediality. For both Young and

Miserable and Reverse Proxy, in

addition to their open confrontations with authority, also nag at the autonomy

of cinema, suggesting its contingency as a composite medium that is necessarily

affiliated with other media. The first emerges from (and returns to) the stage,

as its frontal compositions and long takes derive from the proscenium view of

the theatre; the second is fully implicated in the aesthetics of the computer

desktop, which paradoxically both obviates the idea of a profilmic world, and

also tenders the computer screen as a key realist space of contemporary

quotidian experience. The overt anti-establishment narratives of both Young and Miserable and Reverse Proxy are matched by aesthetic

gestures that turn cinema back on itself, making clear the intermedial

relationships of the images we see, and exhorting cinema to push through the

screen. How can two vastly different approaches to filmmaking take aim at the

same reality? How can shared political aims adopt such varied aesthetic modes?

Jovens Infelizes ou

um homem que grita não é um urso que dança (Young and Miserable or A Man Screaming is Not a Dancing Bear)

Young and Miserable opens

in striking fashion, with an echoing Beckettian voice speaking from the void,

assuring us (and itself) that ‘there must be something, or else there’d be

nothing but total despair’. Text on the screen announces the scene to follow as

‘Segment 6 – Epilogue – The Cabaret of the Dead’. The first image is of a red

curtain, in front of which a woman’s face suddenly appears in close-up,

seductively singing down the camera at us, and breaking the fourth wall from

the very beginning:

|

|

Let us blow all of

it up, blow it up

So the world can

rise anew, rise anew

Destruction is in order if one wants to start anew. |

Lest

the address to camera seem to have lost its power to shock, a cut augments the

effect by revealing the woman’s body, from which, surprisingly, both arms and

legs have been violently removed – clearly a result of the destruction she

advocates. ‘I am a child of frustrated processes, of unfinished stories’, the

woman tells us.

|

|

She

is soon replaced by various other men and women on stage (all from the troupe),

each of them bearing scars or other signs of violence, and delivering their own

mysterious lines about the action to come. As with the very few scenes in this

black-and-white film that are shot in colour, this introduction clearly

designates the theatre as a fantasy space, in this instance situating the

action in the afterlife. Here we are at the very beginning, then, but already

at the end – these characters are dead, but what has killed them?

The

answer is given in the next episode – ‘The Final Work’ – one of six in reverse

chronological order, and each with their own subdivisions indicated by a number

of literary intertitles – ‘Lost Illusions’, ‘Portrait of the Artists as Young

People’, ‘The Myth of Sisyphus’. Now, those from the cabaret stage stand

together united as a group in an empty office space, masked and holding

weapons. ‘The whole thing has been fully rehearsed’, one shouts to the police

out of frame, ‘but it is not a goddamn play! This is real, this is life!’ They surround a male hostage (soon revealed

to be the governor), who is seated and bound by ropes with a black cloth

covering his face. Strapped to his torso are several sticks of dynamite. One of

the group reads a prepared statement to a camera,

stating forcefully that no negotiations will be entered into, as the group

gather in a circle, and detonate the explosive device. The screen fades to

white.

|

|

The

film proceeds to locate the causes for this violent event, the last resort in a

political climate in which no other action seems particularly effective –

destruction necessitated by the desire for renewal. We are introduced to the

group, a motley assortment of young men and women – including an imposing

Basque man and a priest – who live together in a São Paulo apartment and engage

in radical performances both in assigned theatre spaces and on the streets.

They divide their time between rehearsals, discussing protest tactics and

aesthetics, partaking in domestic and familial quarrels, and engaging in group

sex; as one of them points out, ‘struggling and partying are different aspects

of the same thing’. We trace their history backwards, finally arriving at the

point at which it all began, in a small bar called the Red Cabaret (an analogue

for the posthumous space at the start).

The

final shot of the film, captured in this bar, is a curious one that also

returns us to the explosive beginning. First, an iconic framed picture of

Eisenstein scrutinizing a film strip, an image that stands as a kind of metonym

for what follows. Then, a pan along the wall, as the camera picks up more

framed photographs: of revolutionary moments, of constructivist posters, and

finally of the main characters surrounding the governor just before he is blown

up – an impossible image as we now know, for this is an event that has not yet

taken place in the film’s inverted sjuzhet.

What to make of this final confounding shot, oddly

slung between joyous memorialization and a certain unshakeable nihilism? Is it

an eternal return that confirms the ‘frustrated processes’ of the contemporary

moment, and even the futility of militant political action altogether? Or a

more optimistic connection between revolutionary gestures past and present?

|

|

|

|

In

the words of its original Portuguese title, Young

and Miserable bears two separate but related reference points that help in

thinking about such questions, and together summarise the film’s political and

aesthetic ambitions: ‘Jovens Infelizes’

is a deliberate nod to ‘Giovani Infelici’, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s famous essay

on the intergenerational legacies of fascism, and suggests the film’s

commitment to connecting past and present; ‘um

homem que grito não é um urso que danca’ (‘a man screaming is not a dancing

bear’) is an oft-cited line from Notebook

of a Return to the Native Land (1939), a decolonialist epic by the

Martinican writer Aimé Césaire. Where the first title points to uneven dynamics

between generations, the surtitle draws attention to the differences between

action and spectacle, a tension emphasised by the work’s attachment to

theatrical performance.

|

|

Writing

towards the end of his life, Pasolini attributed the unhappiness of the youth

in the nineteen-seventies both to the failures of their forebears (in their

capitulation to fascism in Italy), and to the limits of their contemporary

situation. The sins of the fathers were visited upon the sons, but at the same

time the new generation was responsible for its own actions. While they may have inherited the legacies of a fascistic regime, they

themselves were to blame for succumbing to the modern fascism of post-war

consumer culture and ‘progress’ more generally – a catch-all category that

gathers both bourgeoisie and proletariat alike in a monolithic vision of

history. (3) The essay is perhaps summed up best by Anna Magnani’s titular

character in Mamma Roma (Pasolini,

1962), who reasons paradoxically – ‘how you end up is your own fault’ – before

adding that ‘the evil you do is like a highway the innocent have to walk down’.

Young and Miserable itself

follows the logic of Pasolini’s text by connecting the vestiges of the 1964 coup

– and its intensification in the form of a more repressive dictatorship from

1968 through 1985 – to the Brazilian dystopia of today (and even after the

film’s release, resonating in the ‘soft’ coup that was Rousseff’s impeachment).

(4) In this, the film apportions most of the blame to the older generation, who

are here represented most obviously in the character of the governor. This is a

man who we discover was something of a radical in his time, and who lived

through the dictatorship, but is now firmly part of the establishment.

|

3. Pier Paolo Pasolini, ‘Unhappy youths’, in Lutheran Letters, trans. Stuart Hood

(New York: Carcanet Press, 1987), pp. 11-16.

4. Adriano Garrett, ‘“Os festivais não podem ser horizonte”, diz vencedor da 19a Mostra de Tiradentes’, Cine Festivais, 17 February 2016. |

But

aside from this familiar trajectory of an idealist corrupted by power, Young and Miserable suggests more

productive links with times gone by. There are other revolutionary heroes worth

remembering – ‘Rosa, Lenin, Che!’ – who once put the

critical stops on the unquestioning onrush of progress, and who return here so

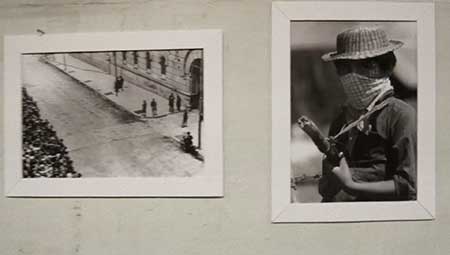

as to rupture the contemporary mood of political malaise. Throughout, there are sequences featuring

black-and-white photographs depicting events of historical and political

significance: of the public display of Che Guevara’s corpse; of the barricades

in the Paris Commune; of riots in May ’68. These pictures flash up at several points

in the film, both as unannounced montage sequences not on the same plane as the

rest of the action, and on other occasions projected in the troupe’s apartment,

as inducements to action. They also feature in the end credits. (5)

|

5. Such images resonate with a similar use of historical

photographs in ‘La sequenza del fiore di carta’, Pasolini’s contribution to the

anthology film Amore e rabbia (Love and Anger, 1969), where they are

deployed in superimposition so as to disrupt the sunny disposition of the

film’s present.

|

While the memories of

historical-political events are clearly important in Young and Miserable, the photographs highlight the film’s

connection to different cinematic lineages: to Pasolini, to La Chinoise (Jean-Luc Godard, 1967), to

early Fassbinder, and to Rivette. (6) Closer to home, the film also invokes the

fleeting spirit of São Paulo’s own cinema

marginal, a brief revolutionary phase in Brazilian filmmaking that reacted

against – on the one hand – the stark realism of cinema novo, and – on the other – a complete surrender to

commercial models of production, both from Hollywood and at home. This period,

which bridged the sixties and seventies and counted Julio Bressane and Rogério

Sganzerla as its most renowned figures, also included a filmmaker who makes a

cameo appearance in Young and Miserable.

This is Andrea Tonacci, whose initial underground films like Bangue Bangue (Bang Bang, 1971) are matched by the undeniable power of Serras da Desordem (2006), his

remarkable anthropological narrative work produced four decades later. In this

brief scene, Tonacci leads a seminar on filmmaking, and states that ‘images are

stronger than this crap we call “product” and “market” and shit like that’,

chiming with Mendonça’s own equivocations about the kinds of Brazilian films

that are the by-products of industrial models and festival circuits. (7)

|

6. Quite coincidentally,

the film perhaps shares most in common with a bold epic that premiered in

Toronto in 2016, and which also imagines an alternative present in which acts

of radical violence might have taken place: this is Ceux qui font les révolutions à moitié n’ont fait que se creuser un

tombeau (Those Who Make Revolution

Halfway Only Dig Their Own Graves [Mathieu Denis and Simon Lavoie, 2016]),

a work of very similar temperament that focuses on a cadre of radical students

who take action during the 2012 protests in Montreal over hikes in university

fees.

7. Garrett, ‘Os festivais não podem ser horizonte’.

|

Tonacci’s inclusion is no accident, as the director

represents, for Mendonça, a rare fidelity to the spirit of cinema marginal that has remained in evidence throughout his entire

body of work. As Mendonça has argued, cinema in Brazil suffered a marked

decline after the coup, especially where it was backed by the new State-funded

company Embrafilme in the 1970s and 1980s. As democracy was finally restored,

the country’s film production began to boom in what is now known as the retomada (‘restart’, ‘rebirth’, but

literally ‘retaking’). But Mendonça believes that national cinema, since that

time, has lost its political compass, and that even the cinema of the Left in

Brazil today practices a tradition of class conciliation that is no longer

worth pursuing (although he doesn’t name a particular film, we might imagine that

a recent work like Casa Grande [Fellipe Barbosa, 2014] would fall into this category). (8)

|

8. André Queiroz and Gabriel Ramponi, ‘Destaque da semana – entrevista Thiago B. Mendonça’, Revista Ensaio.

|

For Mendonça, it was theatre rather than filmmaking

in Brazil that remained more consistently committed to radical gestures, and

which offered an unparalleled experience of collective artistic creation. (10)

Young and Miserable itself grew

organically from the stage, and from a more de-institutionalized performance

culture, as a series of ‘invisible theatre’ gestures that brought the stage to

the streets. (11) Its very movement of becoming-film enacts the passage between

two different art forms; as Alain Badiou would say, ‘subtracting’ theatre from

itself by turning it into something else. (12) This process of subtraction is

developed clearly in several scenes throughout. On the one hand, theatre

arrives in the film courtesy of a few clear set pieces: the pre-credits

sequence with the ‘Cabaret of the Dead’; a musical number comparing New York to

São Paulo; and a fantastical interlude featuring the three male actors

crucified on Calvary in a parody of Waiting

for Godot (Esperando Gordão,

originally a 2015 Mendonça short film in its own right).

|

9. Aimé Césaire, ‘Cahier d’un Retour au Pays Natal’, in The Collected Poetry, trans. Clayton

Eshelman and Annette Smith (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California

Press, 1983), p. 45.

10. André Queiroz and Gabriel Ramponi, ‘Destaque da

semana – entrevista Thiago B. Mendonça parte II’, Revista Ensaio, In São Paulo in the late nineteen-nineties, the

‘Arte Contra Bárbarie’ movement (Art Against Barbarism), drew together several

fringe theatre groups, whose work provided aesthetic reflections on alienation,

exclusion and the exploitation of labour even in times of apparent economic and

political stability. See Iná Camargo Costa, ‘Reflections on Theater

in a Time of Barbarism’, trans. Maria Elisa Cevasco, Mediations Vol. 23 No. 1 (Fall 2007), p. 71.

11. Queiroz and Ramponi, ‘Thiago B. Mendonça parte II’.

12. Alain Badiou, Handbook

of Inaesthetics, trans. Alberto Toscano (Stanford, CA: Stanford University

Press, 2005), p. 79.

|

Aside from these performances, there is also the

more consistent proliferation of long, almost static mid-shots that frame the

action of many scenes as though they were unfolding on a stage (or at the

barricades). There is also some use of frontally-oriented, planimetric

compositions in the film, shots that confine the actors to spaces that appear

flat, spaces with entrances and exits, the exteriors of which are firmly

excluded as though not part of the same narrative plane. This particular apprehension

of spatiality gives the film a deliberate sense of claustrophobia – the feeling

that characters may depart from the screen space, but that such a move would

motivate a cut in the action. Most of these scenes take place in the troupe’s

apartment, in which the mise en scène intimates various aspects of the outside

world: the riot shields emblazoned with protest slogans, or the drawings on the

wall detailing scenes that occur elsewhere in the narrative.

|

|

Notable in such scenes is their length and stillness,

the slowed cadences of the editing and camera movement as compared to the

generally more active shots of the São Paulo streetscape. And in all of this

the apartment tableaux effectively evoke the myriad tensions between theatre

and cinema to which critics have returned at different points throughout the

last century. For instance: the unified performance of the stage actor against

the assembled individual performances of the film actor (Walter Benjamin); or, the

continuous space of the theatre and the discontinuous spaces of cinema (Susan Sontag).

(13)

Certain differences between the two art forms are

impossible to reconcile, but what is most interesting about Young and Miserable is the way the

troupe’s performances already anticipate and frame these differences. In one

scene titled ‘Culture is Big Business’, they stage their central performance in

a studio space for a small audience, drawing theatre, cinema and politics

together while leaving the tensions between them unresolved. The show itself

involves multiple fragmentary elements, like the opening cabaret act:

aggressive denunciations of the governor (who is represented by a mannequin);

raunchy burlesque comedy involving the troupe’s landlady and her lover; and a

Carmen Miranda parody. On top of this, moving image technologies inhabit the

space. One of the troupe roams around the audience,

taping both the actors and the audience and projecting the images live on a

large screen. Shown here as well is footage of the governor rejecting the

tactics of protestors, and urging citizens to show some decorum. Most

fascinating of all, perhaps, is the play’s end, when a female cast member has

her throat cut on stage, before the lights fall. Then, upon leaving the

premises, the audience encounters her again, bloodied and fierce as she accosts

them on the street: ‘I am the headless woman whose screams still echo through

the memories of the have-nots!’

|

13. Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Its

Technological Reproducibility: Second Version’ in The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and

Other Writings on Media, Michael Jennings, Brigid Doherty, Thomas Y. Levin

(eds.), trans. Edmund Jephcott, Rodney Livingstone, Howard Eiland, et al.

(Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknapp Press of Harvard University Press,

2008), pp. 19-55; Susan Sontag, ‘Film and Theatre’, The Tulane Drama Review, Vol. 11 No. 1 (Autumn 1966), pp. 24-37.

|

|

The

bemused audience saunters off into the night while, riding high on the

achievement, the troupe ventures to an empty cathedral nearby, where they

partake in an orgy upon the altar.

Theatrical

performance here extends its jurisdiction into churches, bars, houses and the

streets. (14) And in contrast to some of the more obviously scripted scenes

that take place in sanctioned theatre spaces, there are various sequences in

which the performances of the actors are foisted upon a public that remain

entirely unaware of the filming process. These happenings unfold in the busy

and unpredictable São Paulo streetscape, with a pretend lynching and a fake

evangelical dance (‘the Holy Cross twerk’) catching the attention of

passers-by. There is also a keen sense of risk that pervades the ‘New York’

interlude, which is staged at night across

the bustling Avenida Paulista, and is clearly affected by the flow of traffic.

|

14. Juliano Gomes, ‘A revolução tem de deixar de ser para existir’, Revista Cinetica, 9 February 2016. |

|

In

spite of the exuberant spirit in which they are conducted, however, the happenings

do not seem to point the way out for the troupe. Whether indoors or outdoors,

the troupe practices what Pasolini might have called – disapprovingly – ‘Scream

Theatre’, designed to scandalize its bourgeois audiences, but perhaps limited

in its pursuit of meaningful political ends. (15) And the players themselves

appear to recognise this shortfall, with one later suggesting that the entire

theatrical tradition should be ‘blown to pieces’ with ‘literal bombs’, while

another – who has devised a version of Brecht’s The Trial of Lucullus – agrees, although she is intent instead on

the less explosive obliteration of the discursive regime that governs the

staging of their plays.

|

15. Pasolini, ‘Manifesto for

a New Theatre’, trans. Thomas Simpson PAJ:

A Journal of Performance and Art no. 85 (2007), pp. 26-38.

|

And

so they look for other means to shock the system, with the troupe venturing

outside to express dissent elsewhere. Here, in a series of documentary scenes,

it is not just the characters, but the actors who are truly involved in several

protests against the World Cup, actively taking part in demonstrations that are

filmed with a hand-held camera. Of course, they are still performing for the

film, and the scenes form part of the narrative, but the complete contingency

of the protest march dictates that nothing here can be known in advance of its

taking place: the infectious chanting that emerges organically from the crowds;

the flows of bodies; the violent clashes with the reactionary police forces.

(16)

|

16. In its incorporation of happenings and protest

marches, Young and Miserable finds a

native precedent in the film O Rei da

Vela (The Candle King [José Celso

Martinez Corrêa and Noilton Nunes, 1982]), which documents several innovative

performances of a play by the famous Teatro Oficina, features the characters

performing in the streets for an unsuspecting public, and incorporates

documentary footage of civil unrest under the Brazilian dictatorship.

|

Again,

these marches fall short of the ultimate, messianic intervention the troupe

craves. But in these scenes, as with the happenings, cinema’s mediation of live

performance at least achieves something noteworthy on aesthetic grounds. Here,

we witness first of all the process of theatre turning into protest and later

radical violence, as the play featuring the marionette governor is later

transformed into an actual political assassination – no longer ‘a god damned

play’ but instead ‘real life’. And it is cinema that ultimately makes this

trajectory possible, cinema that renders legible the relationship between the

various different fragments of the narrative. As Mendonça recalls, the

theatrical beginnings of Young and

Miserable eventually called for the ‘more concrete realism’ of cinema,

carving out an entire realised world of its own that (although not present to

its audience) is more complete than that which is offered by the proscenium

stage. (17) Even when the artifice of performance is easily

detectable, the camera still holds the promise of capturing the grain of the

real in those who pass in front of it. At once, the film

is invigorated by theatrical performances, extending and connecting them to a

world, and distributing them as images to wider audiences.

|

17. Queiroz and Ramponi, ‘Thiago B. Mendonça parte II’.

|

|

These

dynamic exchanges between theatre, cinema, and politics emerge again in one

particularly memorable scene in the film. In the midst of a riot that turns

ugly, the troupe flee, entering an empty movie

theatre in which a film plays to no audience: it is Carlos Reichenbach’s Alma Corsaria (Buccaneer Souls, 1993), about the marginalised in São Paulo. (18)

In the fascinating seven-minute scene by Reichenbach, a book launch is taking

place in a pastry shop, when a man dressed in work clothes sits down at a grand

piano and plays a superb rendition of Debussy’s ‘Claire de Lune’. The camera

focuses in on the variety of faces gathered at the launch, each of them deep in

personal reflection, and listening so intently that they ignore the presence of

a bodybuilder just outside, flexing his muscles along to the music. In Young and Miserable, the troupe also

stares in rapt attention at this scene, unconsciously miming the characters on

the screen in front of them. They stand together on the stage as the enormous

images form before them, first in black-and-white and then gradually in the

warmth of colour: a chance meeting of political activists and performers on the

margins, together in a space situated between theatre and cinema, between dream

and reality.

|

18. Mendonça holds Reichenbach in high regard: he studied with the director’s daughter, Eleonora, and after meeting him was inspired to become a filmmaker in his own right. When Reichenbach died in 2012, Mendonça eulogized him in the magazine he edits for Coletivo Zagaia. Mendonça, ‘Silêncio, o cinema esta de muto. Ao mestre Carlos Reichenbach’, Zagaia em Revista, 15 June 2012. |

Proxy Reverso (Reverse Proxy)

Where Young and Miserable at times presents

its characters in a series of long takes in imitation of the theatrical stage, Reverse Proxy participates in a

different logic of continuous image-making, with the permanence of the computer

screen designating less cuts than a high turnover of content within the unbroken image. In this way,

the film draws cinema into a different, non-cinematic space. On the one hand, the immobile interface is

immediately foreign to the cinema; its old arsenal of tools for creating

temporal montage – cutting, panning, zooming and the like – instead spatialise

the movement of the plot by way of competing windows, tabs and desktops on the

screen. (19) On the other, it may be equally true to say that cinema is

becoming (or has become) foreign to itself, entering (or already ensconced

within) a ‘post-cinematic’ shift. Where film’s pride of place as the cultural

dominant had already been usurped by television in the post-war years, the

‘death’ of celluloid – coupled with the ubiquity of computer and network

technologies, and the rise of streaming services – has prompted many to

consider the medium with fresh eyes this side of the new millennium. (20)

The idea of watching a film that takes place on a

laptop has quickly emerged from the once-unthinkable act of watching a film on

a laptop (let alone on a smart phone). Today there are a growing number of

movies now embracing the interface as the totality of their cinematic space,

the beginning and end of the worlds they map out. The most well-known in this

group is the horror film Unfriended (Levan Gabriadze, 2014), which focuses on a group of teens haunted by a

mysterious cyber-presence – their friend who committed suicide after being

shamed in a YouTube video they shot and uploaded. In Unfriended, as in other films of its ilk, there is an emphasis on the peculiarities of social media and of uniquely modern communicational forms. At the same time, however, the desires, the dynamics and

the motivations all begin and end in spaces external to the world wide web,

reaching ‘beyond new technologies to capitalist social relations as a whole’.

(21)

A related paradox of the desktop movie is that

although it is a relatively new form, its procedures and affective intensities

stem from a piece of hardware for which the operations and aesthetics are

completely familiar. The computer interface is not in any way strange to the

majority of contemporary viewers, plenty of whom are on a daily basis inured to

the rhythms and tempos of a multitude of screens – notifications, alerts,

demands, and deadlines commute across a variety of platforms that reside in

devices located in bags, pockets and purses. But the experience of watching

such films is still disorienting, both in the initial encounter with the

desktop image (especially with the uncanny experience of watching it on a

laptop), and also in the gathering pace of images, sounds and text that assault

our senses. For, instead of the classical procedure of suture that binds the

viewer to the image and orients our gaze toward particular characters or

objects in each shot, our viewing practices in desktop films are, as Shane Denson

has put it, ‘dispersed’ – our eyes forced to scan the screen since it consists

of multiple different windows, all simultaneously competing for our attention.

(22) In Reverse Proxy, this effect is

redoubled (at least for those viewers who are unable to read or speak

Portuguese), since the film’s subtitles add another layer of text to an already

crowded screen, at times translating the dialogue spoken between characters, at

others the headlines of news articles or messages written in chat windows. And, as

those messages are often retracted or edited mid-sentence, this involves a good

deal of deleting and re-typing (a recognisable habit), with letters and words

vanishing from the screen just as our scanning of the lines has caught up with

the rest of the action.

|

19. Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press,

2001), pp. 322-326.

20. Steven Shaviro, Post-Cinematic

Affect (Winchester, UK and Washington: Zero Books, 2010), pp. 7-8.

21. Johanna Isaacson, ‘“Unfriended” Unpacks

Cyber-Sociality’, Blind Field: A Journal of Cultural Inquiry, 16 February 2016.

22. Shane Denson, ‘Post-Cinematic Affect, Collectivity, and Environmental Agency’, medienitiative, 2 April 2016. |

In this atmosphere, the experience strangely

divides the viewer in two, casting doubt over which are the most important

words and images on the screen. There is at once a desire to read and see

everything, to know the totality of this space, and in so doing to consider how

such a film is put together (it was filmed by way of screen capture in real

time at different points throughout 2014). But as this becomes an impossible

task, there is also a willingness to lose oneself in the flood of pixels,

bracketing out much of the apparent white noise that hovers around the frame,

while trying to read for the central plot. (23) Rarely does the centre of the

screen play host to the most important pieces of information in the film;

iMessage and Skype are relegated to opposite corners of the frame; the

acousmatic dialogue (although centred through the use of subtitles) often

chimes or clashes with text appearing simultaneously in chat windows.

|

23. In contrast to

the film proper, the trailer for Reverse

Proxy guides the flow of images, as we zoom and focus on certain parts of

the screen, and are given what the directors deem to be the most important

components of the film via a series of cuts, accompanied by an ominous

soundtrack firmly hitched to the rhythms of the editing.

|

Reverse Proxy revels in this

environment, one in which non-purposive browsing and a perpetually roaming gaze

might reign supreme, but also where sniffing out even the faintest of

connections between two distant points might spark a flurried and deliberate

opening of multiple tabs. The opening images and sounds immediately key us into

the possibilities and contingencies of a desktop narrative, and to the rhythms

of the film itself. Here we have a montage of grainy footage of civilians

jumping from the World Trade Centre Towers on 9/11, a 3D reconstruction of the

two plane crashes in New York from that day, and the scene of the alien attack

in Independence Day (Roland Emmerich,

1996), all of which are eerily accompanied by the sounds of electronic musician

The Caretaker’s Patience (After Sebald) – itself a reworking of Schubert’s Die

Winterreise – composed as the soundtrack for Grant Gee’s 2012 film of the

same name.

|

Perhaps because of their disorienting quality, or

the noteworthiness of their content (or both taken together), these scenes are

completely mesmerising. But no sooner have we witnessed these opening exchanges

than the image suddenly shrinks, revealing (not unlike the start of Young and Miserable) the wider frame

that will make some sense of the sequence. It is with this cut – one of the

very few in the film, and one that coincides with the resizing of a window on

the screen – that we are first apprised of the fact that the images are housed

on a Mac computer. We are now aware that the 9/11 footage has been sourced from

YouTube, and is being played simultaneously on different windows on the screen.

The music, we soon discover, has been playing through iTunes, part of a

diegetic (and immaculately hip) soundtrack that rotates constantly throughout

the film, featuring the likes of Death Grips, Cat Power, Grimes, John Maus and

Arcade Fire. In tune with this rotation of music, we also bear witness to a

cavalcade of different programmes and websites, from the digital distribution

platform Steam, to the incognito browser Tor, to Facebook and Wikipedia and the

dark web of Silk Road. We come across the online role-playing game Vindictus and a version of Mortal Kombat modified for the Mac (the

end credits provide a list of the software used in the film in order of appearance).

And, if you look hard enough, at one point you might even see a pirated copy of

Derek Jarman’s Caravaggio (1986)

lined up in the downloads queue.

|

Although a great surplus of information passes

before us in the film, the images and sounds are harnessed in a particular way

and towards particular plot-focused ends. In control of this entire interface is Davi Reis, a programmer and our first-person protagonist,

whom we never see, and indeed whose voice we only begin to hear around

one-third of the way through. Those first videos have been sent to him by a

conspiracist friend and budding journalist, Luis Pires, who tries to convince

Davi that the truth of the attacks has been concealed from the public, and who

later makes similar claims about the plane crash that killed the Brazilian

presidential candidate Eduardo Campos in 2014. (24) Although Davi is not quite

so ready to follow Luis in his paranoid speculations, he is certainly aware of

the invisible machinations that maintain structures of power in his nation and

in the wider world. In minor acts of resistance, Davi reads and shares articles

from alternative media sources detailing events in the election, watches a

YouTube mashup that turns the candidates’ debate into nonsense, and

strategically doctors images of the World Cup protests on Photoshop.

|

24. Davi reads a

report about the death of Campos while watching the mile-high heist centrepiece

from The Dark Knight Rises (Christopher Nolan, 2012), a staged mission involving a plane crash.

|

While the very mise en scène of the film possesses

the ability to conjure potentially any images or footage or pieces of text from

anywhere in the world, there is also a local context to the work. The film is

of course inspired by organisations like Wikileaks and Anonymous in their

extrajudicial movements towards greater freedom of information. But Reverse Proxy also emerges from a Brazil

that in June 2013 showed how the use of the internet – and in particular social

media – could counteract the stranglehold of monolithic media organisations

like the Globo Group, by helping to coordinate a series of protests and taking

the country’s ruling elites by surprise. (25)

The national specificity of the film’s political

concerns emerges over the course of eleven separate episodes (initially

non-chronological, although later adhering to a linear progression), with each

incorporating a temporal leap, and divided by a black screen with the episode’s

number. (26) Early on in the piece, Davi and Luis hatch a plan to leak

sensitive documents from the market research company Vox Populi, which will

reveal underhanded manipulations of certain polling figures in the lead-up to

the October 2014 federal elections. (27) Davi secures a job at the company

through Luis’ ex-girlfriend Verônica, and is soon able to access and release

the information that proves the corruption endemic to the Brazilian democratic

process. The effect of the leak is felt immediately, as the São Paulo stock

market crashes, and the credibility of all three candidates – Rousseff, Aecio

Neves, and Marina Silva – is called into question. However, the police soon

trace the leak back to Molotov, a news site run by Luis. Davi is then arrested,

and is later found hanged in his cell (accompanied by a suicide note, but still

highly suspicious). These final events are not relayed to us by Davi but

instead come courtesy of a big reveal at the end of the film. Or rather, two

big reveals: what we have just been watching for the last 75 minutes is

actually a screen capture of Davi’s entire desktop, now viewed on another

computer in Adobe Premier Pro, a program evidently operated by a detective. But

then, just when the game appears to be up, the detective’s computer is hacked

before our eyes, as an unseen programmer takes control of his cursor and

keyboard, and leaves messages confirming that further cyber-attacks will take

place: ‘for each of us you take down, a thousand will rise’. Experimental

collage film turns political thriller, turns found-footage horror.

|

25. Andre Singer, ‘Rebellion

in Brazil’, New Left Review no. 85

(January-February 2014), p. 35.

26. Aside from

several digital glitches added in post-production, these are the only points at

which the continuous image is cut.

27. Life mirrored art earlier this year, when a front page report by Folha de São Paulo, the largest newspaper in Brazil, ran a distorted poll that suggested that a majority of the population wanted Rousseff to resign. Glenn Greenwald and Erick Dau, ‘Folha’s Journalistic Fraud Far Worse Than We Reported Yesterday: A Smoking Gun Emerges’, The Intercept, 21 July 2016. |

This trick immediately brings to the fore the

film’s own production process, such that we are now not only occupying the

perspective of the detective and then the hacker, but we are also seeing what

the directors would have seen when they edited their work into its current

appearance. But more than this, the ending plays on our expectations about the

relative sovereignty of the human over unseen computational processes. At one

point in the film, we can see that Davi’s desktop background is an image of

Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above

the Sea of Fog (1818), a conventional shorthand for the Kantian individual

at the centre of his own sublime experience, but here an ironic analogy for the

individual who loses control over the flow of information in his online

environment.

|

Such an image also makes sense of the film’s title:

a proxy is a type of server that masks the identity of a user, so that the user

might access resources held by a separate remote server, without revealing

their identity or location. By contrast, a reverse proxy privileges the remote

server itself: one of its various functions is the ability to feed resources

from the remote server through the proxy server, and back to the user, thus

masking the remote server’s identity. Reverse

Proxy pivots on the difference between these two modes of networked

communication, at first suggesting the hacker’s secret inviolable control over

the situation, before reminding us of the relative magnitude and complete

uncertainty of the online environment in which he operates. For much of the

film, the first-person perspective of Davi appears as a kind of proxy for the

audience, and it is through his eyes (more or less) that we view the images on screen.

However, the final scenes give the lie to the belief that Davi has been our

anchor point throughout it all, as we are presented with the two additional

meta-perspectives. The programmer, the detective, the hacker, the viewer: all

are ultimately lost in a technological abyss, a recursive image of depth before

which the computer, and the film, must terminate.

|

Long before this penultimate shot, it is clear that

the apparent ‘flatness’ of the desktop interface not only hides a far more

complex series of operations within the machine itself, but also betrays a

vital connection to the world outside the computer, and to the users who

coordinate its various processes. There are several ways in which the software

displayed on screen indexes the presence of a human operator, and emphasises

the fact that computer use is a kind of cyborgian activity that involves

physical and affective labour, with a user necessarily working on and with text,

sound and images. But this is not immediately clear, as the machine crowds out

any obvious signs of human life. As opposed to a film like Unfriended – in which footage of the various characters using Skype

was shot with a series of GoPro cameras (28) – the screen capture of Reverse Proxy contains no live footage

of its actors, relying instead on the sounds of their dialogue, the keystrokes

that make text appear on screen, the movements of the cursor, and the

appearance of alternate desktops conjured by a four-fingered swipe of the Mac’s

trackpad. The nominal first-person perspective limits the gaze to the screen

space and prohibits any kind of physical movement, but Davi’s existence

registers both in the grain of his voice and in his necessarily haptic,

embodied manipulations of the laptop.

In addition to these points of contact with the

human, there is the fact that this point of view is moored in particularly

masculinist patterns of online consumption: Davi creates a Vindictus avatar called ‘ChelsManning’ and augments its female body

to his liking; he browses XVideos for porn fetishising women in hijabs; Luis

sends Davi nude photos of Verônica after much pleading from the protagonist;

Davi later follows a suspect link to the site ‘MyEx.com’ where he unexpectedly

doxes Veronica by publishing those photos. While certain aspects of his private

online pursuits simply form part of Davi’s leisure time, there are other, more

sinister elements of his behaviour that are neither motivated by the exigencies

of the plot, nor predicted by his political leanings. As with the tense

communal living situation that serves as the hotbed for radical thought and

action in Young and Miserable, here

the knotty commingling of the personal and the political is in plain view, with

disparate windows featuring ‘private’ content sharing the non-hierarchical

screen space with Davi’s ostensibly ‘purer’ hacktivist manoeuvres.

|

28. Matt Mulcahey, ‘How to Fake a Movie That Takes Place Entirely on a Laptop: DP/Producer Adam Sidman on Unfriended’, Filmmaker Magazine, 13 August 2015.

|

More than troubling the noble political

interventions of Davi and Luis, the uneasy distribution of images on the screen

speaks to the liminal experience of watching the film. For a work that

celebrates the unfocused and the ephemeral, and in which there are few

appreciable differences between the cinematic image and the computer screen, Reverse Proxy directs our attention to

its porous frame, potentially co-extensive with the laptop screen upon which we

might be viewing it. The democratic assortment of windows on the screen draws

images, text and ideas into fresh relations, and redrafts the space of the

cinema screen in accord with the everyday space of the desktop. In this we can

find a completely realistic film, one that bears a close resemblance to

quotidian cybernetic experience, where the screen is living, is life.

Football in

absentia

What is so far missing from this discussion is the

event that helped to bring these films into being: the 2014 World Cup. But it

is right that this is the case. While the political projects of both films

are in part galvanised by the injustices of the competition, what is (mostly)

occluded from each is the sport itself, a spectacle whose images would without

a doubt consume all other images within its purview. (29) Somewhat

surprisingly, scenes of the matches are absent altogether from Reverse Proxy, save for one in an

article that Luis sends to Davi: footage from Germany’s 7-1 defeat of Brazil in

the semi-finals has been uploaded to the ‘domination’ category of Pornhub, a

displacement (or amplification?) of the host nation’s shame effected through

reproducing the offending images in a ‘taboo’ online space. Young and Miserable presents the absent

spectacle in another way. In this case, where montage separates a street march from one of Brazil’s victories

in the competition, the World Cup is clearly marked as a divisive event in the

national consciousness – one of the troupe watches the game in awe while

another simultaneously voices his anger at the military police. Here are two

completely different films that take aim at the same reality, but which offset

the gravitational pull of the spectacle by refusing to reproduce it directly.

Instead of the event of the football match, other modes of performance enter

the frame, and direct the flow of images. Here: theatre, political protest,

violence. There: computing, networks, information. A cinema looking for answers

over the uncertain horizon of Brazil.

|

29. Another recent Brazilian film adopts a similar

strategy in a very different register: Sergio Oksman’s documentary O Futebol (2015) follows a reunion

between an estranged father and his son (the director) during the competition,

with the pair committed to watching every game of the Cup together. However,

footage of the matches is almost completely eliminated from the film, as the

focus falls entirely on the filial relationship.

|

Stefan Solomon’s research is supported by: |

© Stefan Solomon 2016. Cannot be reprinted without permission of the author and editors. |