Source Hunting in a Dreamscape

|

The art historical past plays manifold roles in the

films of David Lynch, as does the history of film. Lynch is special, as a film

artist whose oeuvre grew, almost as a mutation, out of a studio art practice.

The primal scene of his cinema, as per Lynch himself, was a moment – standing

before a painting in progress – in which he was seized by the almost

hallucinatory desire to see it move and to hear the wind in it. Lynch’s primal

scene – an oft repeated narrative; part of his autobiographical legend – seems

a variant on Wassily Kandinsky’s explanation of the

origin of abstraction in his work: a magical misapprehension of a painting seen

upside down in the dark one night. But Lynch’s is also the primal scene of

cinema itself. Among the spectators of the Lumière brothers’ first films were those

entranced by the kinetic impression of ‘the ripple of leaves stirred by the wind’,

in the background of a scene. They were taken by cinema’s presentation of ‘nature

caught in the act’. (1) The sound of the wind stirring the leaves of trees is a

salient feature of key scenes of voyeuristic fascination and existential

uncertainty in Blow-Up, Antonioni’s 1966

international art house sensation, seen on U.S. screens in the months before

David Lynch turned to film. The cinema’s capacity to go beyond nature, to

create a phantasmal dynamization of the image, was

one of the qualities that enthralled Lynch’s forebears, the Surrealists. Long before Blow-Up, the wind that stirred the Lumière

leaves emerges uncannily from Buñuel’s mirror in L’Age d’or (1930).

|

1. A journalist, Henri de Parville,

quoted by Siegfried Kracauer in his Theory of Film: The

Redemption of Physical Reality (New York: Oxford University Press, 1960),

p. 31.

|

|

| L’Age d’or (Luis Buñuel, 1930) |

The unnamed woman played by Lya Lys, violently separated from and dreaming of her lover (Gaston Modot), sits before the mirror at her vanity. Instead of

her own visage – in an image Dudley Andrew aptly connects to René Magritte – she

faces a sky and clouds. (2) The sound of a cowbell, associated with her desire

(the animal she has just found inexplicably occupying her bed) and the bark of

a dog (in the crosscut action, associated with her lover’s violent, animal

lust), mix with the sound of wind and then, uncannily, that wind penetrates the

plane of the mirror and blows into the room, stirring the hair of the daydreamer.

The plane of the mirror stands, too, of course, for the screen, the membrane

that separates viewer from spectacle. This exemplary Surrealist scene, with its

lyrical and weird fusion of sound and image, dream and reality, sexual longing

and violence, rejoins the separated lovers in a spatiotemporal realm unique to

the cinema, a realm in which desire transcends the mirror and the lens. This is

the realm in which the best of David Lynch’s films unfold.

|

2. Dudley Andrew, ‘L’Age d’or and the Eroticism of the Spirit’,

in Ted Perry (ed.), Masterpieces of

Modernist Cinema, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006), p. 118.

|

|

|

|

Oww God, Mom, the Dog he Bited Me! (1988), to give just one especially striking example,

evokes the mysterious, quasi-abstract psychodramas of Surrealist painting of

the 1920s; its iconography and its title suggest a hybrid of Miró’s Dog Barking at

the Moon (1926) and Tanguy’s Mama,

Papa is Wounded! (1927). Eraserhead’s (1977) black-and-white horrors, uncanny from

beginning to end, and aspects of The Elephant

Man (1980) – particularly its first shots – evoke Surrealist photographs

such as Dora Maar’s Pere Ubu (1936), Hans Bellmer’s grotesque ‘dolls’, and images seen in Bataille’s journal Documents in the 1930s.

|

|

|

| Dora Maar, Pere Ubu; Eraserhead |

Lynch may have been familiar with Maar, Bellmer, Bataille and Documents, or not. No matter; influence

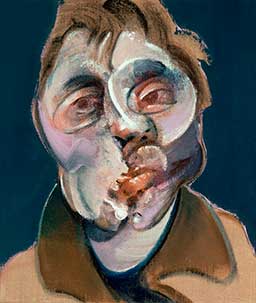

is only one road to affinity. Lynch’s affinity to Bacon – much discussed,

acknowledged by the artist, and evident across media – can, however, be

attributed in part to influence, and Bacon did read Documents and utilise its illustrations.

|

|

|

|

| The Elephant Man; Francis Bacon, Self Portrait, 1969 (private collection); Carte de visite portrait of Joseph Merrick, ca. 1889 (Royal London Hospital Archives) |

As I have discussed elsewhere, Lynch’s practice, like

Bacon’s, depends on a sensational formal affect and thematic focus on bodily

and psychological extremity and abjection:

|

| While it is

impossible to imagine either Bacon’s or Lynch’s work without access to the

basic concepts and vocabulary of psychoanalysis – the unconscious, dream-work,

sexuality and its discontents – to the extent that psychoanalytic

interpretation offers an explanatory narrative, it is resisted and inadequate. As with the Surrealists, Bacon and Lynch revel in the darkness of

the conceptual spaces probed by psychoanalytic thought, not in the light of its

expository, explanatory, or therapeutic power. (3)

|

3. Susan Felleman,

‘Two-Way Mirror: Francis Bacon and the Deformation of Film’, in Angela Dalle Vacche (ed.), Film, Art, New Media: Museum Without Walls? (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), p.

231.

|

Moreover, their interest in the irrational extends to

narrative itself, which Bacon rejects wholly, while Lynch undermines and

destabilizes its conventions. Bacon’s deformations, his palette and his

theatrical ‘staging’ of many of his works appear and reappear in an array of

circumstances in the films of Lynch. The face of John Merrick (John Hurt) in The Elephant Man is, in fact, very like

a three-dimensional rendering of a Bacon portrait. This may seem like a

problematic comparison, since the protagonist’s deformations were closely based

on physical and photographic impressions of the historical Joseph Merrick

(called John in the film). Bacon, however, was an avid gleaner of photographic

images from a huge array of sources, and revelled in medical and scientific photographs

(among others), including those from the nineteenth century, so may himself

have known and employed the image of Merrick.

There is little point in trying to enumerate the many

scenes in Lynch’s colour films that seem indebted to Bacon, as the influence is

a very long-standing and internalized one. Composition, colours, textures,

lighting and staging often reflect Bacon’s sensibility, even where citation or

homage may not have been intended. The door in the back of a Lynch interior, a

dark or schematic denotation of a mystery beyond the scene, is a frequent

iconographic nod. Bacon employed blur and a kind of liquid or shifting contour,

and occasionally streaks, to bring something temporal and almost cinematic into

the unnerving, glazed figural field of his paintings; reciprocally, Lynch’s

films often have moments in which time feels suspended or slowed in order to

body forth a kind of painterly tableau or abstraction. Even Lynch’s signature

soundscapes somehow manage to evoke Bacon, the disturbing, non-diegetic layers

of noise functioning almost as the equivalent of certain disturbances in the

field of a painting.

|

Another art historical facet of film is the art object

as an element of mise en scène. Because the world of

live action cinema consists of an excess of concrete things – more or less considered

and controlled by production design (depending on location and other factors) –

art objects of various kinds are frequently to be found in films. The relation

of such objects to the actors and action is various and thorny to research and

to theorize; sometimes they are foregrounded, often not. The relation between

director, production designer, art director, set decorator and other crew

involved in the construction of the profilmic scene is

various, too. Moreover – with the exception of objects in films about art and

artists, as well as some other films where the object takes on a narrative role

– there may be no element of mise en scène more variously

visible. (4) Certain categories of viewer – artists, art historians and

interior designers, for instance – may be more likely to notice an object,

while it may appear incidental, or remain wholly invisible to others. But conscious

attention and recognition are not the beginning and end of the impact of an art

work in film. As with soundscape, which often exerts a subliminal force upon

narrative, physical details can, along with visual style, inflect and inform a

scene.

David Lynch’s feature films and television serials typically

do not abound with art objects; they are themselves such objects, in a sense.

When one does encounter art objects, they are often reproductions. Certainly – whether

one can identify them or not – it is hard to miss the reproductions of iconic classical

statues of Venus – the Venus de Milo and the Medici or Capitoline Venus (similar

examples of the Aphrodite Pudica type) – prominent in the sparsely furnished,

red op dream spaces of Twin Peaks’ (1990-1991)

Black Lodge. However, based on a quick survey of internet comments, the two are

oddly likely to be mistaken for one: the latter (Pudica),

who coves her breasts and pubis with her arms, is often taken for the former

(Milo), who has no arms. But who would notice the small framed female nude – probably

a reproduction of a nineteenth-century academic painting – seen just

momentarily on a wall in a scene in Marietta Fortune’s nouveau-riche interior,

near the beginning of Wild at Heart (1990)? Who would recognize the painting of a dolorous young woman seen for

mere seconds a few times in Aunt Ruth’s place in Mulholland Drive (2001) as a once-famous portrait of a once-infamous

girl named Beatrice Cenci? (5)

Each of these intertextual appearances

is different in terms of its interface between narration and viewer. In Wild at Heart, the little picture seen

in passing is a minor detail of set dressing. Hanging on a wall near a

thermostat, a light switch, and a clock with chimes, we see it when Marietta (Diane

Ladd) has just hung up the receiver after receiving Sailor’s (Nicholas Cage)

call from prison for Lula (Laura Dern).

|

4. Theorization and analysis of different aspects of art in narrative cinema are the subjects of my books, Real Objects in Unreal Situations: Modern Art in Fiction Films (Bristol: Intellect Books, 2014) and Art in the Cinematic Imagination (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006).

5. The painting long regarded

as being by Guido Reni and of Beatrice Cenci is almost certainly neither. See

Barbara Groseclose, ‘A Portrait Not by Guido Reni of

a Girl Who is Not Beatrice Cenci’, Studies

in Eighteenth-Century Culture, Vol. 11 (1982): pp. 107-132.

|

|

|

An immediate cut to a medium close-up of Lula at the

top of the stairs, conjures her in a posture that echoes that of the nude in

the picture, her arm raised over and bent behind her

head, her eyes closed. Although she is standing, the pose denotes languor. In

fact, in historical artworks suggesting sleep or bondage – including ancient

ones, such as the semi-recumbent Hellenistic sculpture of a sleeping satyr

known as The Barberini Faun, as well as Michelangelo’s so-called Dying Slave – the posture also signals a kind of sexual

availability or surrender.

|

|

| Michelangelo. Dying Slave, 1513-15 (Louvre) |

By essentially rotating an odalisque or sleeping

figure from a recumbent position to the vertical, the pose adds conspicuous

display to sexual availability. Variants on it are common in academic nudes,

especially rather prurient female nudes of the late 19th century, in

which little thematic excuse was needed to justify the unnatural pose.

Ultimately, the prevalence of the motif – adopted typically by mythological (e.g.

Venus Anadyomene) and Orientalist fantasies – naturalizes

what is actually a rather odd posture (Picasso adapted it, restoring some of

its strangeness, for two of the figures in his Les demoiselles d’Avignon). In

transferring the pose to Lula, and repeating it throughout Wild at Heart, Lynch denaturalizes it and, with somewhat Buñuelian effect, uses it to signify l’amour fou (mad love): the passionate

attachment between Lula and Sailor across space and time, in defiance of their

enforced separation. The picture on the wall need not appear for more than a

few moments to ground this postural attribute of Lula’s in the realm of

material culture and convention. Somewhere between art and kitsch, the picture

is a kind of 19th century pictorial correlative of Wild at Heart itself, a film suspended

histrionically between art and exploitation. Wild at Heart draws upon the three ‘body genres’ Linda Williams

distinguished according to the psychosexual fantasies that structure them and

their implicit audience and effect – horror (shiver), pornography (sexual

arousal) and melodrama (tears) – braiding them together into an over-the-top,

road-tripping paean to American pop culture: an exploitation picture for every body! (6)

Twin Peaks’ Venuses are part

of a dreamscape and so, it turns out, is the Beatrice Cenci picture, although – critically – the (first time)

viewer probably does not know that until late in the film. Thus, these are

images that can float free of material culture; if they can be said to ground

their respective scenes at all, finally they ground them in fantasy. Venus (Aphrodite),

the goddess of love, presides over the oneiric atmosphere of the Black Lodge.

Appearing in two forms, she is resonant with cultural and intertextual meaning but also symbolic in Lynchian terms.

|

6. Linda Williams, ‘Film

Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess’, Film

Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 4 (Summer, 1991), pp.

2-13.

|

|

|

The Venus de Milo in particular is not only one of

Western civilization’s most iconic images and said to epitomize female beauty

(as with the Medici and Capitoline examples), she is

also an image of an armless woman. Although consciously one may not associate a

fragmented and treasured antiquity with human deformation, in the unconscious,

the meaning of an object is overdetermined. The

statue can embody sexual love, sexual objectification and dismemberment at the

same time. Indeed, such layered meanings only add to the mystery, allusion and

unease of Lynch’s scenario.

This is (not) the girl

So it is with the supposed Beatrice Cenci portrait, long attributed to the Italian Baroque

master, Guido Reni (1575 – 1642), a reproduction of which hangs in that

apartment near Sunset Boulevard in Mulholland

Drive. Beatrice Cenci (1577 – 1599) was a young Roman noblewoman, beheaded

in 1599 for having conspired in the murder of her despotic and abusive father.

The story of the patricide, ensuing trial and execution is full of lurid

sensationalism and pathos. It is almost a David Lynch picture unto itself:

tyranny, abuse, incest, conspiracy, murder, tears, decapitation.

An object of near veneration for over a hundred years, the picture, as much as

the story to which it was attached, was a source of fascination and inspiration

for some of the many artists – among them Shelley, Stendhal, Hawthorne, Artaud and Moravia – who spun the sordid flax of the Cenci

story into literary gold. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s play The Cenci (1819) was inspired by his encounter the year before with

the picture in the Palazzo Colonna, where in the last quarter of the 18th century it had come to be regarded as a portrait of Beatrice Cenci, and

associated with Guido Reni. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s reaction was typical of the

Romantic investment in the picture and the woeful tale it conjured: ‘the very

saddest picture ever painted or conceived’. (7) So, just as in Twin Peaks the Venus de Milo can

function at one and the same time as an image of consummate beauty and a

dismembered body, the Beatrice Cenci picture is both an image of a tragic

beauty and a decapitated head.

Neither the picture

nor the place in which it hangs in Mulholland

Drive, however, is exactly what it seems. Although there are clues that Betty’s (Naomi Watts) arrival in Los

Angeles and entry into her Aunt Ruth’s apartment are dream events (‘I just came

here from Deep River, Ontario and now I’m in this dream place!’ she exclaims), for

the most part the direction and style defy the impression of a dream, an

impression so often and so effectively constructed through techniques of

lighting, mise en scène, sound and cinematography in

Lynch’s films. Indeed, by restricting obviously oneiric style to a couple of key

sequences in the first part of Mulholland

Drive – Dan’s (Patrick Fischler) vertiginous dream

of Winkie’s and the enigmatic Club Silencio sequence – the film defers the revelation of its

basic secret, that the first two hours of its narrative are entirely a dream,

one largely composed of an array of wishes built upon day traces of the events

seen in the last twenty-plus minutes (essentially reversing the structure and

sequence of The Wizard of Oz [Victor

Fleming, 1939]). Since many interpreters of Mulholland

Drive – scholarly and amateur – have exhaustively analysed the textual, intertextual, and Freudian structures by which this clever

scenario proceeds, I shall refrain from doing so and focus on the presence of

the ‘portrait not by Guido Reni of a girl who is not Beatrice Cenci’.

The picture is at first glance just one of very many

details of mise en scène in Aunt Ruth’s apartment, probably the film’s most minutely and

realistically dressed set. This richness of detail is one of the aspects that

belie a dream aura, which Lynch typically effects by isolating

a few salient and incongruous elements in an unnatural, theatrical space. At

Aunt Ruth’s, décor that suggests a well-heeled, single woman of a certain age

tastefully fills the Mission style rooms. Behind the leather couch, with its

throw pillows, where several key scenes are played, is a console with an array

of silver-framed black-and-white photographs. On the walls are framed prints

and paintings, in the passage that leads to the bedroom hangs the Cenci picture

– as a reproduction of an old master painting, probably the least realist

element in the set – surrounded by built-in bookshelves, a lamp, a vase, a

small, vivid green figurative sculpture and other decorative objects.

|

7. See Groseclose.

|

|

In the bedroom, bath and dressing area are more framed

pictures, including the poster for Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946) that, seen in the mirror, lends the amnesiac Rita (Laura Harring) her name, as well as an appropriately and finely

cluttered vanity, a carpet, a luxuriously made bed, bedside tables and lamps, and

a stunning, artisanal, modern polychrome wardrobe, with rather expressionist figures

in relief.

There is no location in the waking events of the

film’s last section that corresponds to this space and no personage is the

waking manifestation of Aunt Ruth, who is established as an actual relation of

Diane’s but a deceased one, an inheritance from whom enabled the aspiring

actress to come to Los Angeles. The space and its contents, then, take on a

more symbolic aspect; rather than representing jumbled traces of recent waking

experience (as do most of the characters and other locations, with obvious

exceptions, such Mr. Roque and his H.Q.), they are presumably

cut wholly from (Diane’s) unconscious cloth. As the site where Diane (also

Naomi Watts) is innocent and talented (as Betty), Camilla (also Laura Harring) needy and vulnerable (as Rita), and their erotic

discovery of and love for one another passionate and pure, the space has the

contours of a wish fulfilment.

|

|

| The painting long regarded as a portrait of Beatrice Cenci and formerly attributed to Guido Reni, ca. 1662 (Rome: Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica) |

And much as Aunt Ruth’s apartment is not hers and finally

not even in narrative terms real, the doleful, turbaned young woman, looking

over her shoulder back into the room at the viewer, is not, in fact, in spite

of the many dreams of her it inspired, Beatrice Cenci. Charles Nicholl ventures that ‘her name was appended to the picture

to lend it a spurious glamour’ and suggests, based on the turban and drapery,

that the painting probably represents one of the Sybils,

oracular women associated with sacred sites of Ancient Greece. (8) Neither is

the painting likely by Guido Reni. Unless an imaginative portrait, it certainly

cannot be both of Beatrice and by Reni, who did not move to Rome until some

years after her death. Moreover, the conceit that she had been painted on the

eve of her execution appears in no historical account for nearly two hundred

years, until the second half of the 18th century, the period in

which the legend of the Cenci became immensely popular. (9) The name Guido Reni

may ring few bells in the 21st century but, according to Barbara Groseclose,

|

8. Charles Nicholl,

‘Screaming in the Castle: The Case of Beatrice Cenci’, London Review of Books, Vol. 20, No. 13 (2 July 1998): pp. 23-27.

(Accessed January 1, 2014.) |

| Even if the

biographical and stylistic arguments for including the portrait in Reni’s

oeuvre are ultimately flimsy, the acceptance of the canvas as his handiwork is

nonetheless explicable. The ascription first gained currency because of the

late eighteenth-century veneration of Reni and the inclination to find his

touch in countless pictures … Indeed Reni occupies in the early travel guides a

place nearly equal to that of Raphael in the hierarchy of Old Masters. (10)

|

10. Groseclose,

p. 117.

|

A burgeoning wave of Romantic sensibility elevated the

gothic horrors and sentimental pathos of the Cenci story from morbid historical

curiosity to absorbing morality tale just as it elevated Reni’s somewhat

anodyne style, due to its emphasis on dramatic emotional affect. The

misattribution of the painting is an effect of these converging epistemic

impulses, itself something of a Romantic wish fulfilment.

In the unconscious, of course, as Freud insisted,

there is no time and there is no negation. Dream images, as displacements,

projections and condensations, are overdetermined. So

the presence of the ‘portrait not by Guido Reni of a girl who is not Beatrice

Cenci’ in Diane’s dream of Ruth’s apartment can and should incorporate any and

all aspects of the picture’s history, metahistory,

composition and style. In a dream, the girl in the picture can be Beatrice

Cenci, a tragic victim of sexual abuse who shall die for committing a justified

murder – an identity that merges with Diane’s own – and a Sybil, the ancient woman with prophetic powers, an identity

manifest in the character of Louise Bonner (Lee Grant), a prophetic neighbour

who seems modelled on a Sybil. The girl in the picture, too, whose eyes ‘are

swollen with weeping and lustreless, but beautifully tender and serene’, as

Shelley wrote, expresses the lachrymose mood of regret that overcomes Diane’s

dream, reaching its apogee in the Club Silencio sequence, in which the two women weep copious tears as Rebekah Del Rio lip-syncs

to her own recording of ‘Llorando’ (a Spanish version

of Roy Orbison’s ‘Crying’).

And, of course, the portrait is something of a

correlative of the headshot, the Hollywood portrait photo that plays a key role

in Mulholland Drive. So, it also represents

Camilla, another murdered girl, whose headshot, accompanied by the words, ‘this

is the girl’, is passed across the table to the hit man by Diane. This is the

day trace for the head shot of ‘dream Camilla’ (Melissa George) being passed

across the conference table to Adam (Justin Theroux) by the thuggish Castiglianes (Dan Hedaya and

Angelo Badalamenti), accompanied by the same line. The

verbal repetition of the line ‘this is the girl’ is echoed in the visual field

by the focal repetition of a backward, over-the-shoulder gaze. This is, of

course, the singular attribute of the pose of the ‘portrait not by Guido Reni

of a girl who is not Beatrice Cenci’. As Lula’s characteristic pose in Wild at Heart seemed to emerge from the

languorous nude in the picture on Marietta’s wall, so too do several resonant

moments in Mulholland Drive reproduce

the distinct posture of the girl in the picture, whose gaze by virtue of its

looking back over the shoulder suggests retrospection, regret and possibly even

longing or ominous foreboding.

|

|

All of these emotions are part of the affect of the

characters who adopt this posture in Mulholland

Drive, most notably in Diane’s dream: Adam, toward whom the camera tracks

as he twice looks longingly back at Betty – whom he has never before seen and

who is standing behind him near the soundstage door – just as he is ruefully

compelled to say of Camilla, ‘this is the girl’; and Diane’s neighbour, the

woman in #12 (Johanna Stein), who – just before the film’s (dream’s) central

crisis – hesitates at the door of Diane’s Sierra Bonita bungalow while Betty

and Rita are inside, then walks away, casting a long worried, ominous glance back

behind her. In the film’s final scenes, we see both Camilla and Diane turn and

look back over the shoulder, too: Camilla at Diane as she leads her up the

(secret) garden path to Adam’s house on Mulholland Drive, and Diane in her

kitchen as she turns to see the apparition of Camilla whom she knows is dead.

So, the ‘portrait not by Guido Reni of a girl who is

not Beatrice Cenci’ is a multivalent image. It is an image whose own dubious

identity corresponds to the multiple and shifting identities in the film, whose

complex history and misattribution interpolate the viewer into a Romantic

fascination with a grievous tale, and whose iconography suggests an altogether

different story of supernatural vision. The portrait is also a formal model for

an evocative leitmotif and affect found in various registers of the film’s

narrative: dream, memory, hallucination. Overdetermined,

it may initially appear a mere prop; it may even have entered the film as one,

but it is in a sense an image into which one can fall and never come out … like

the blue box that gives visual form to the unconscious in Mulholland Drive. As with each of the citations and allusions that

telescope the film’s profound intertextual engagement with reflexive masterpieces of a

cautionary cinephilia – Sunset Boulevard (Billy Wilder, 1950), Vertigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958), Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966) and Contempt (Jean-Luc Godard, 1963)

– the picture on the wall at Aunt Ruth’s is like a window that opens onto another

story, another world, perhaps into a dreamscape beyond. As a static image of a

woe-begotten girl frozen forever in a backward glance, this window onto another

world paradoxically reverses the impulse of the painter before his canvas,

seized by the desire to see it move, to hear it breathe. On the wall at the

back of the scene – at the other side of cinema – a painting suspends action,

drawing the motion picture toward stillness and silence (silencio), and what lies beyond.

|

© Susan Felleman 2016. Cannot be reprinted without permission of the author and editors. |